By now you’ve probably heard the story, that eagle-eyed readers perusing the most recent edition of the Oxford Junior Dictionary spotted the disappearance of a number of nature-based words. Words like blackberry, acorn, minnow, and fern—gone. Why? To make room for words from the lexicon of digital technology, such as analogue, broadband, cut-and-paste, and voicemail.

Petitions ensued with over 50,000 signatures garnered. An open letter to Oxford University Press, the publisher of OJD, signed by Margaret Atwood and twenty-seven of her well-published compatriots, urged “that a deliberate and publicised decision to restore some of the most important nature words would be a tremendous cultural signal and message of support for natural childhood.”

We recognise the need to introduce new words and to make room for them and do not intend to comment in detail on the choice of words added. However it is worrying that in contrast to those taken out, many are associated with the interior, solitary childhoods of today. In light of what is known about the benefits of natural play and connection to nature; and the dangers of their lack, we think the choice of words to be omitted shocking and poorly considered.

The Guardian

And then there’s this:

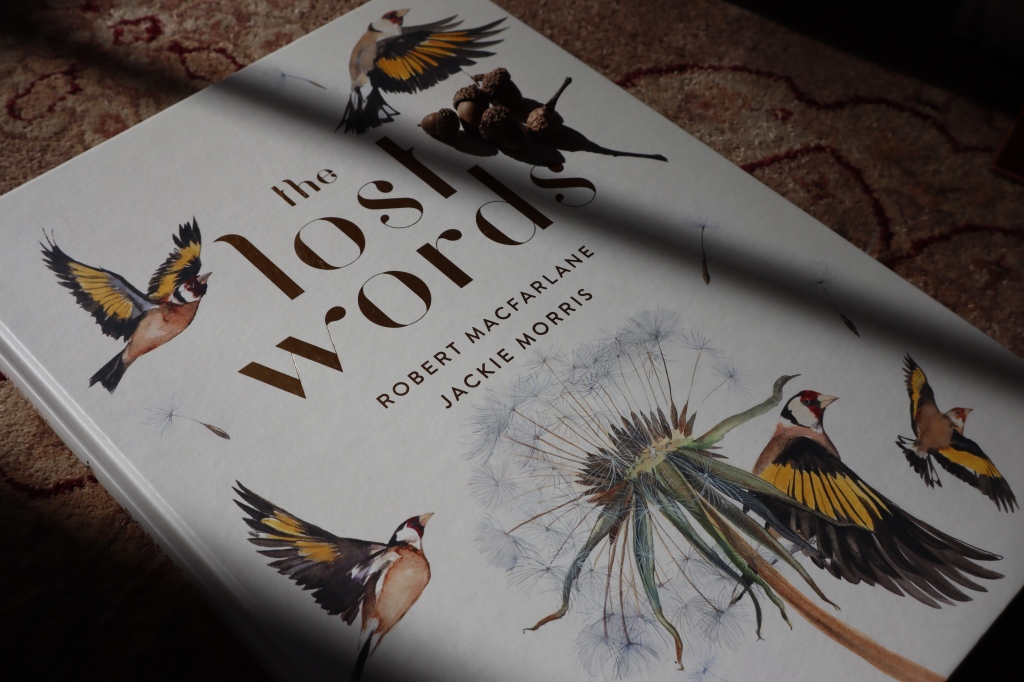

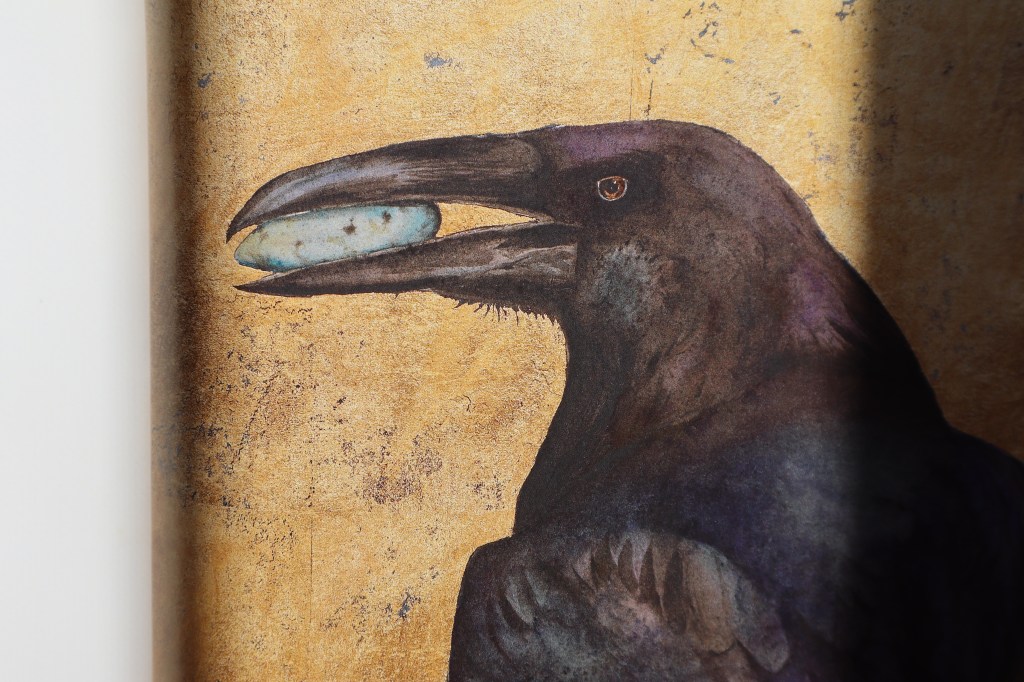

The Lost Words, a large, enchanting book by British writer and University of Cambridge Professor Robert Macfarlane, with illuminating watercolors by Jackie Morris, celebrates twenty of the nature words that had been removed from OJD. The Lost Words is a “spell book,” poetic celebrations of each of these words that are meant, according to Macfarlane, to be spoken aloud, encouraging young and old readers alike to rekindle their connections to kingfisher, otter, weasel, and wren, beckoning them back into common use with something akin to poetry or song.

Speaking of song:

We humans don’t often head for the watercolors or the piano when we find ourselves up against something we oppose, to say nothing of the deeply disturbing or even horrifying. Not every problem lends itself to the elevated response, though memories of Vera Lytovchenko playing her violin in that Ukranian cellar as bombs dropped overhead remain clear in my mind.

I often think the gap in our speaking about and for justice, or working for justice, is that we forget to advocate for what we love, for what we find beautiful and necessary. We are good at fighting, but imagining, and holding in one’s imagination what is wonderful and to be adored and preserved and exalted is harder for us, it seems.

Ross Gay, in conversation with Krista Tippett

I only know that when I come across this kind of elevated, transcendent response, I’m so deeply moved, so indelibly touched by what’s possible, for the human spirit, for our world and our future. Art can do this, as it so often has, reminding us of what we’re made of, the stuff of stars.