It’s a humid, sunny Sunday afternoon here in the Midwest, the steady clock of August ticking away in the background. I’m remembering in a palpable way the end of summer as a kid before heading back to school, hanging onto and savoring the sights, scents, and feel of what I now recognize as a completely immersive, full-bodied reverie of life. I want so much for my grandchildren to know this in their own little bodies and I want to trust that this multi-sensory experience of summer will triumph over any attempts, digital or otherwise, to dwarf that headlong, full-throttle dive into nature, called by nature herself, that children and grandchildren (and, really, all of us) are hard-wired to do.

Morrisonville was a poor place to prepare for a struggle with the twentieth century, but a delightful place to spend a childhood. It was summer days drenched with sunlight, fields yellow with buttercups, and barn lofts sweet with hay. Clusters of purple grapes dangled from backyard arbors, lavender wisteria blossoms perfumed the air from the great vine enclosing the end of my grandmother’s porch, and wild roses covered the fences. On a broiling afternoon when the men were away at work and all the women napped, I moved through majestic depths of silences, silences so immense I could hear the corn growing. Under these silences there was an orchestra of natural music playing notes no city child would ever hear. A certain cackle from the henhouse meant we had gained an egg. The creak of a porch swing told of a momentary breeze blowing across my grandmother’s yard. Moving past Liz Virts’ barn as quietly as an Indian, I could hear the swish of a horse’s tail and knew the horseflies were out in strength. As I tiptoed along a mossy bank to surprise a frog, a faint splash told me the quarry had spotted me and slipped into the stream. Wandering among the sleeping houses, I learned that tin roofs crackle under the power of the sun, and when I tired and came back to my grandmother’s house, I padded into her dark cool living room, lay flat on the floor, and listened to the hypnotic beat of her pendulum clock on the wall tickiing the meaningless hours away.

~ Growing Up, by Russell Baker

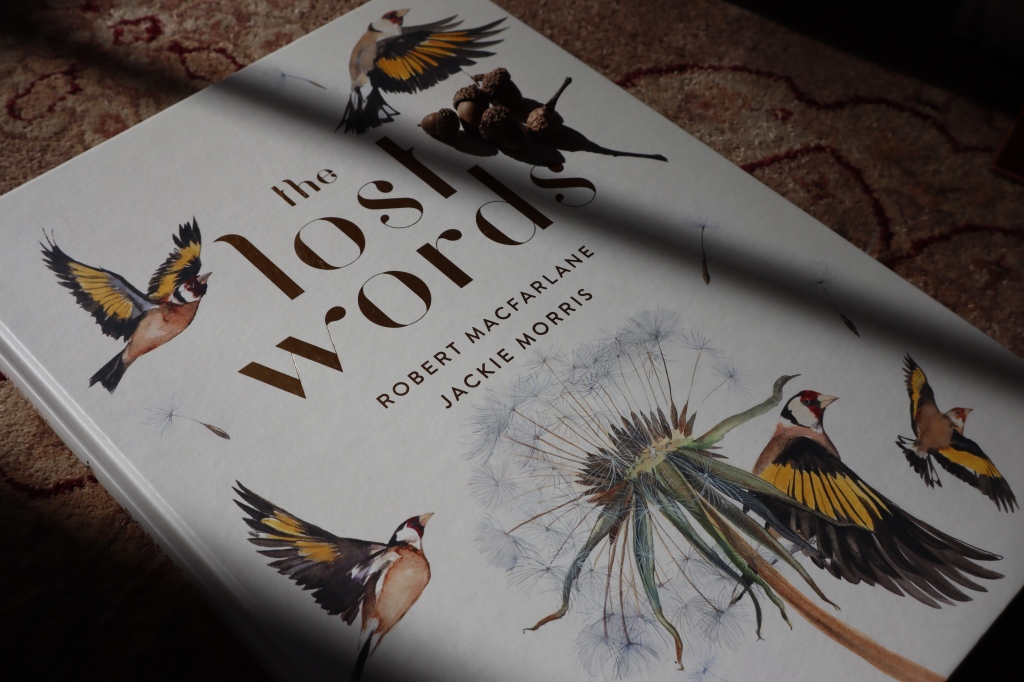

With our young now up against unworthy, addictive opponents for their attention and engagement — quantity over quality, shiny, electrifying, superficial objects on screens that keep them hungry and unsatisfied, yet compelled by misplaced hope to keep coming back for more — one antidote, tried and true, ancient, even, and deeply, dependably gratifying, is any trek into the great outdoors, including and perhaps especially right out the back door.

It wasn’t all that long ago that my 9 y.o. grandson and I were out hunting frogs in the yard, both of us gripped by the ribbit sound coming from the garden along the driveway. With the sun setting and our hour-long attempt leaving us regrettably empty-handed, I asked him what he thought about heading in for a bath.

“I think it’d be a complete waste of time.”

Kids are preternaturally, irrepressably drawn into nature, their very biochemistry assuring them that they are at home here. This isn’t a misread. Their young bodies are telling them something primordially true. The neurochemistry of screen time is an altogether different experience, one that pales in comparison to that deeply elemental embrace of Mother Earth, an invitation which says, to kids and to all of us, “You belong here.”

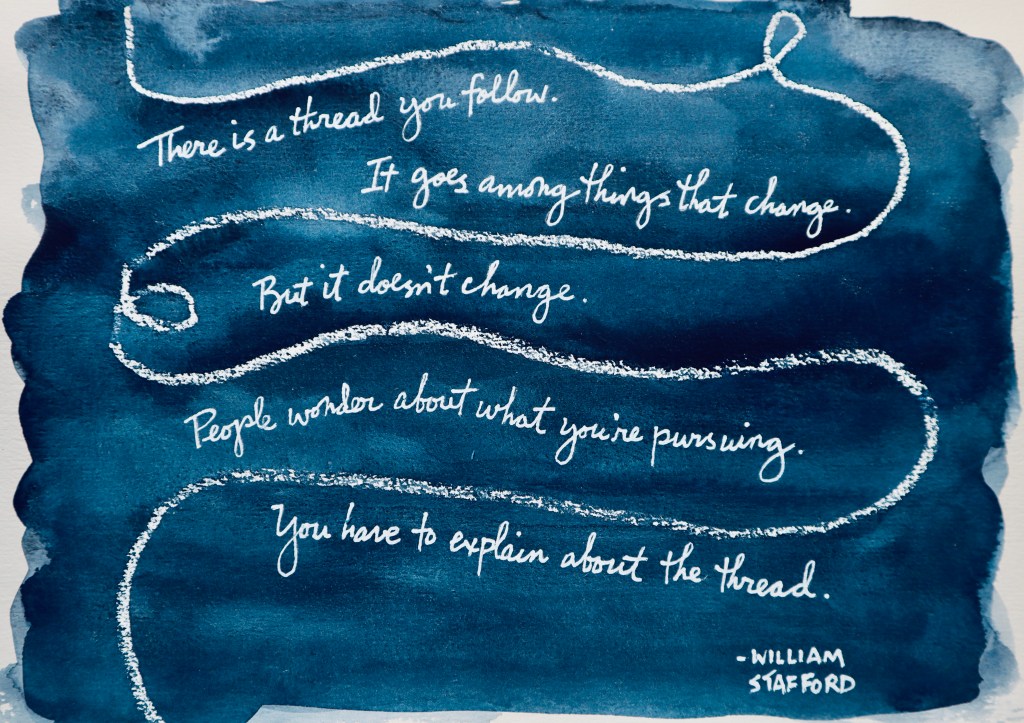

Wherever I am, the world comes after me. It offers me its busyness. It does not believe that I do not want it.

~ Mary Oliver, in Why I Wake Early

Like many of the last generation to remember childhood without devices, I see what’s about to be lost here, a reverie so worthy of preserving, not only for our kids’ and grandkids’ sake but for the sake of the future of our species.

To be in a state of reverie is to inhabit multiple layers of our consciousness all at once, to be fully aware of every bodily internal feeling while hazily hearing and seeing every ambient sound and sight: to be present in this time now while inhabiting the timeless, employing the mind to re-interpret the future and even re-imagine the past. The word reverie recalls to each of us the luxuriant sense of rest we might feel in front of an open fire, perhaps even nodding off, of the body rested and resting deeper, while all the time acutely aware of the sound of rain brushing against the window, the logs crackling, and the sound of children playing mutely in the distance.

~ Consolations II: The Solace, Nourishment and Underlying Meaning of Everyday Words, by David Whyte

Autumn’s heading our way here in the Midwest and Mother Nature, together with that ancient call that comes from deep within our own minds and bodies, invites you and me and all of us to slow down, to empty our hands, and to step out the back door–as David Whyte suggests, “Everything’s waiting for you.”